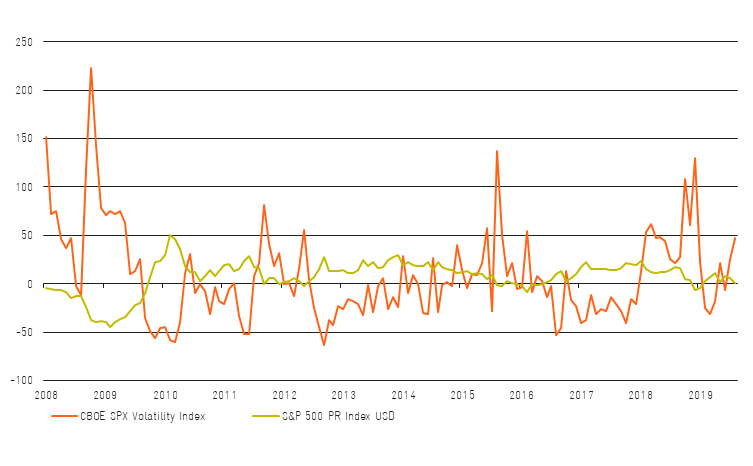

Active management has fallen out of favour among investors, reflecting changing investor preferences and the scars of the Global Financial Crisis, which have led investors to shun stock pickers and more elaborate strategies in favour of lower-cost, vanilla products. Investors today are focused far less on alpha generation, with its goal of outperforming benchmarks, and are now far more content in generating the majority of their returns from index funds or similar passive strategies.

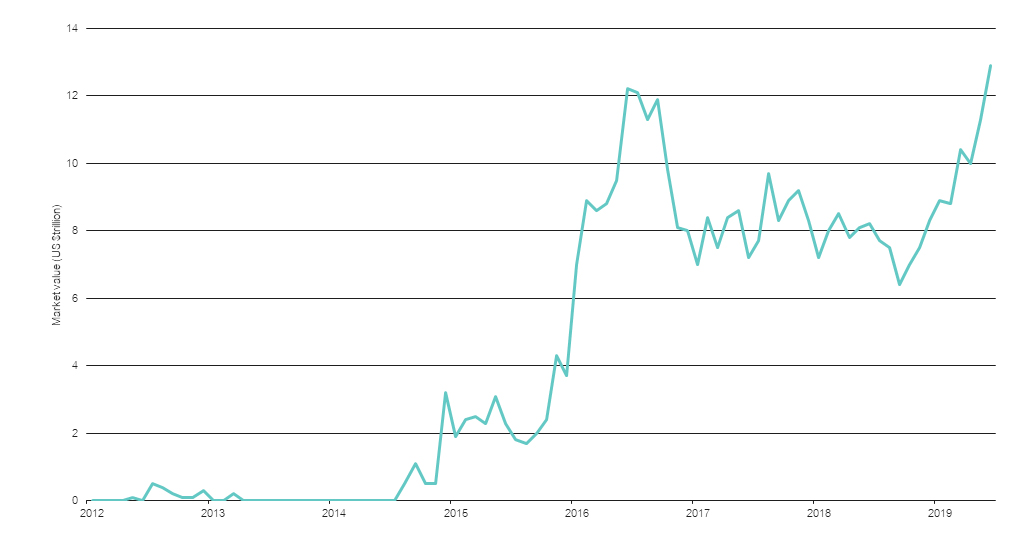

The growth in passive management has been astonishing. In the last five calendar years, investors moved US$1.5 trillion into funds managed by Vanguard, one of the world’s largest managers of passive strategies. Blackrock, the second largest passive manager, took in US$685 billion over the same period. Vanguard now manages close to US$4.0 trillion globally in passive strategies and on average owns around 7% of every listed US company, according to Bloomberg data. As passive managers continue to suck up funds, active managers are struggling to get a positive message through.

Passive managers don’t apply any security selection, meaning the money simply flows into passive or index strategies that replicate benchmarks like the S&P/ASX 300 Index in Australia or the S&P 500 Index in the United States, with Exchange Traded Funds making it easier than ever before for investors to gain relatively cheap passive exposure.

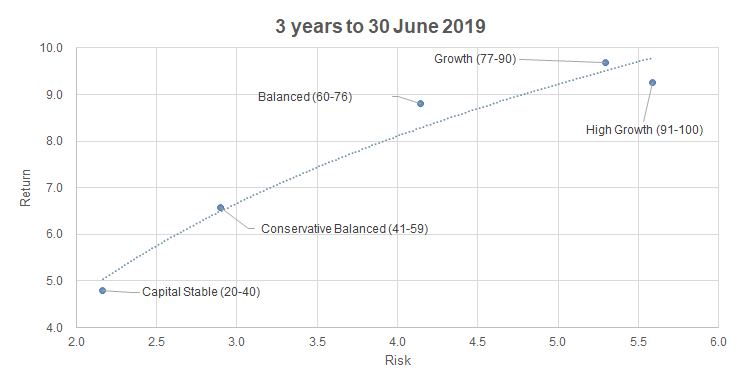

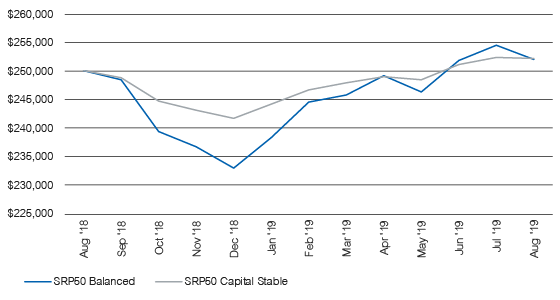

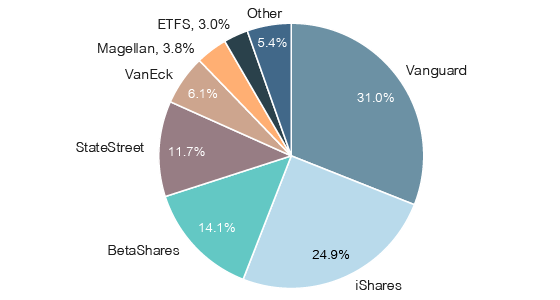

At its core, passive investing is a momentum strategy. It buys more of those stocks that go up in price and sells more of those that fall in price. Passive strategies tend to work best when financial markets experience strong upward moves in share prices. Passive management is used mostly in the portfolio management of equities (Australian, Global and Emerging Markets) and fixed income (Australian and Global) and have given rise to the major ETF providers that currently dominate the market (see chart below).

FUM share of Australia’s major ETF providers (August 2019)

Source: ASX, Lonsec

The beta rally has put active managers in the shade

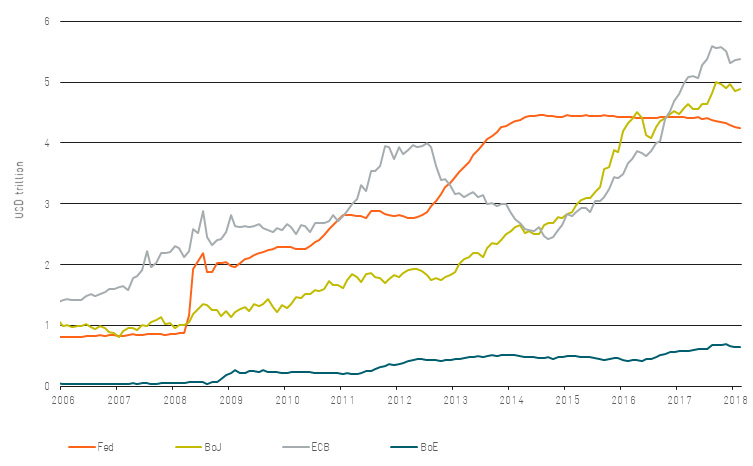

The post-GFC period has been characterised by strong equity market returns, but given the length of the bull market to date, investors are questioning how long this situation can last.

Given the inevitable cyclicality of financial markets, the one thing that’s certain is that strong markets will not last forever. In a low return environment, market beta may end up providing disappointing returns, making alpha a valuable contributor to portfolios.

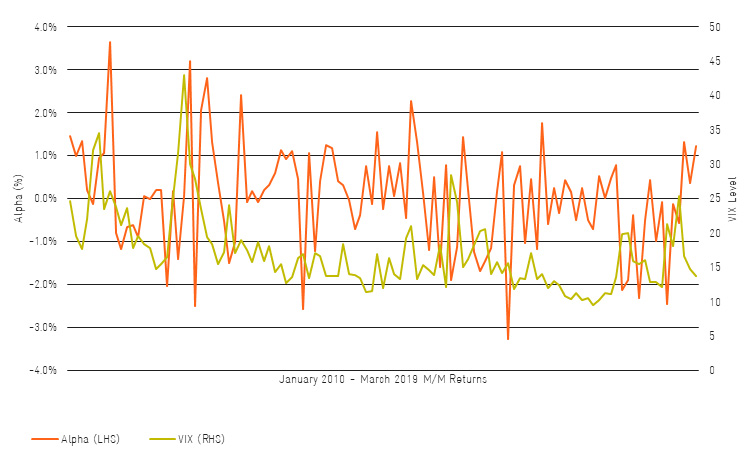

The aim of active management is to be an additional incremental return source, above market returns. Alpha doesn’t scale well with beta, meaning it becomes a smaller percentage of returns when beta is very high. This is the environment we find ourselves in, so we would expect beta to do well and for seekers of alpha to struggle. But even taking a broader view, the case for active management does not appear great.

The hard truth is that most active fund managers underperform benchmarks constructed by index committees. One of the world’s most widely used benchmarks for assessing US equity fund performance is the S&P 500 index. The committee looks at only a handful of criteria when looking to add new stocks to the index, including: liquidity, financial viability (four consecutive quarters of positive earnings), market capitalisation (must be greater than US$6.1 billion), and sector representation (the committee tries to keep the weight of each sector in balance with sector weightings of the S&P Total Market Index of eligible companies). Changes to the index are made when needed.

The S&P committee does no macroeconomic forecasting, invests over a long-term horizon with low portfolio turnover, and is unconstrained by sector or industry limitations, position weightings, investment style, or performance pressures. Yet this straightforward strategy has generally outperformed active fund managers.

Some active managers can consistently outperform

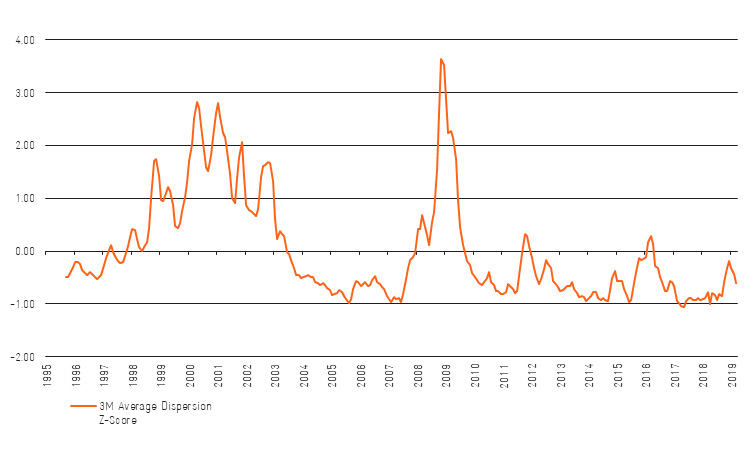

If alpha were easy to find, it wouldn’t exist. There are three general sources to generate excess return for investment portfolios: strategic asset allocation, tactical tilts within asset classes (including opportunistic investing), and superior fund manager selection. While opportunistic investments tend to be episodic alpha generators in portfolios, the biggest long-term drivers of alpha are asset allocation and manager selection.

Even as managers have struggled to generate alpha, a significant number of managers are still generating returns in excess of market indices. The key is having the right resources and the right approach to find them. Average active fund managers tend to underperform industry benchmarks, but the best fund managers outperform over longer time frames.

There’s a deep body of research that looks at how investors can gain an edge by identifying active fund managers that are able to tap sustainable sources of alpha. Research indicates that to meaningfully outperform, it is often helpful to find active fund managers with a portfolio that looks significantly different to the benchmark they are attempting to beat (i.e. they have a high degree of ‘activeness’).

In the financial literature, there are numerous studies showing that the average active fund manager underperforms the benchmark index after fees. However, research presented in 2006 by Martijn Cremers and Antti Petajisto of the Yale School of Management introduced an idea called Active Share. This is a new method of measuring the extent of active management employed by fund managers and is a useful tool for finding those that can consistently outperform. By analysing 2,650 US equity funds from 1980 to 2003, Cremers and Petajisto found that the top-ranking active funds—those with an active share of 80% or higher—beat their benchmark indices by 2.0–2.7% p.a. before fees and by 1.5–1.6% p.a. after fees.

Active share aims to measure the proportion of a manager’s holdings that are different to the benchmark. It is calculated by taking the sum of the absolute value of the differences of the weight of each holding in the manager’s portfolio versus the weight of each holding in the benchmark index and dividing by two. For a long-only equity fund, the active share is between 0% and 100%. The active share for fully passive strategies that replicate an index is 0%, and more than 90% for strategies that are very different to the benchmark index.

As you might expect, the portfolios of active, high-conviction fund managers will diverge significantly from the benchmark, and will frequently incur volatility relative to benchmark returns. However, this differentiation provides investors with the opportunity to add value over the long term.

What to look for when assessing active managers

Skilled managers with high active share have shown a higher tendency to outperform the market. Investors that tilt towards active managers with high active share have a greater chance of outperforming. They tend to be smaller fund management organizations, often where the founder is an investor first and invests his or her wealth alongside external clients, bringing their investing acumen to a portfolio of funds.

Active managers with high active share tend to maintain this high level consistently over time. This proves useful when conducting analysis to help identify managers that are likely to outperform in the future as well. While some of these managers may not have beaten the index in recent periods, when there are dislocations in markets, these managers will be well positioned to generate long-term returns above the fees they charge.

Active share by itself does not indicate whether a fund will outperform an unmanaged benchmark. There are other important aspects to consider when conducting manager due diligence. Here are a few things you should consider:

- Find out as much as you can about the fund’s culture and process. Outperformers see investing as a profession and not a business. Examine the fund’s investment philosophy to see if it is consistent and lived out through the fund’s investment decisions. Does the manager exercise patience and discipline?

- Successful active fund managers have low portfolio turnover with long holding periods of at least four years versus roughly one year for average performing funds. This is a useful metric to look at when assessing a fund’s buy/sell discipline. Another strong indicator is for active managers to add to stock holdings when market pricing improves, rather than giving in to agency behaviour of selling into a falling market.

- Alpha generators are high conviction stock pickers. This means their portfolios are concentrated in their best ideas, leading to a higher level of ‘activeness’ and differentiation from the benchmark.

While there are active managers that are persistently generating alpha, finding them is not a simple task. For investors that are committed to generating long-term outperformance, it’s critical to have the right resources in place to identify these managers. A world class research effort is required to be able to identify and evaluate those managers that can generate consistent outperformance from the thousands of managers out there.

Historically, high valuations in a range of asset classes including equities, sovereign bonds, credit and unlisted assets mean future beta returns are expected to be lower. This will make it a challenging environment for investors to meet their investment objectives. For those with the knowledge and capacity, finding alpha can help bridge the gap.