The Indian growth story – underpinned by strong demographic tailwinds, a stable political environment, reforms introduced by Prime Minister Narendara Modi’s govt and a booming private sector – has gained increasing prominence in recent years.

Recently however, the country has gathered negative media and regulatory attention due to the controversy surrounding one of its most significant businesses, the Adani Group. A bruising report by US-based short-seller, Hindenburg Research, has raised allegations ranging from the improper use of debt to stock manipulation and outright fraud using offshore tax havens for money laundering and siphoning. The result has been a share price rout (exceeding USD 120bn) wreaking havoc on the sprawling empire of billionaire Gautam Adani. More broadly, it has raised darker questions about India’s credibility as a global growth engine and a destination for international investors.

A billion-dollar empire

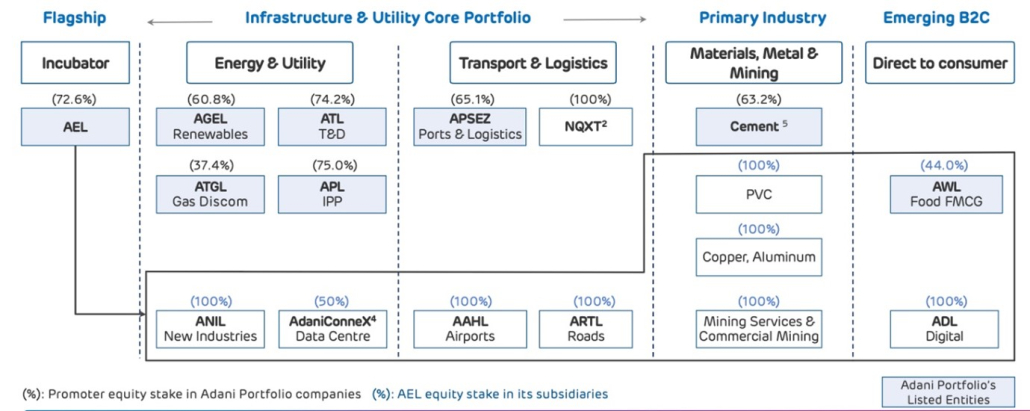

The history of one of India’s largest conglomerates and the world’s second richest man (for a brief period in 2023) can be traced to the humble beginnings of the ‘Adani group’ as a commodity trading business in Gujrat (1988). The company subsequently listed on the stock market in 1994, as Adani Exports, and later entered the edible oil business. Initially regionally concentrated, the Adani Group has grown into a USD 29bn (FY22 revenue) and USD 280bn (market cap, November 2022) nationwide conglomerate with seven publicly traded firms involved in energy, industrial, logistics and lately media. With the exception of Adani Wilmar (food processing) and Adani Digital (media), the underlying businesses share some common characteristics. First, they are infrastructure businesses, and second, they are increasingly related to energy specifically green energy and gas transmission/distribution. While each of these businesses is operated by a stand-alone Adani company, they all flow through the holding entity, Adani Enterprises.

Adani Portfolio overview – January 2023

The rise and success of the Adani Group has been equated to the success of 21st century Corporate India and Modi’s vision and economic model for the country. However, this report uses the Adani’s example to highlight some of the weakest links in this economic framework impacting the country’s growth ambition.

All in the family

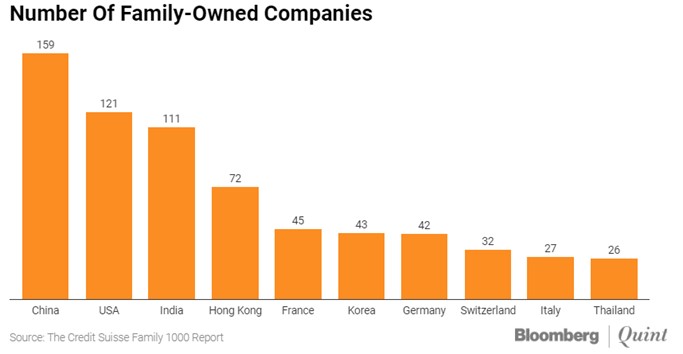

The Adani companies are tightly held by the family that runs them. Shareholding filings available on the National Stock Exchange of India (NSE) provide average promoter holdings across the seven listed companies at c. 73%. Family-owned companies are synonymous with the Indian economy. Roughly 70% of the publicly traded companies and 85% of private firms in India are owned by their founding families to various degrees. Since 2001, the average proportion of shareholdings by promoters for businesses listed on the NSE has been stable at around 50%. Globally, India ranks third highest in terms publicly listed family-owned companies in the world (Credit Suisse Research Institute’s 2018 – CS Family report) behind China and the US.

Suffice to say, the Indian economy depends heavily on these family group businesses, for its sustenance and growth. Investment in family-owned public businesses is generally spoken of highly for their commitment and unified leadership; management stability, vision and long-term goals and focus on sound financial stewardship.

However, Adani’s example illustrates the risks inherent in these businesses. Paramount amongst these is a reluctance to relinquish control via equity dilution, external management, or an independent board presence. This aversion to loss in equity can also at times lead to a love for debt financing which if taken to extremes can result in a spill over like Adani. Minority investors in these businesses also assume the risk of an opaque corporate governance framework leading to exploitative behaviour such as excessive compensation, self-dealing, expropriation of assets, and related party transactions.

Befriending the powers that be

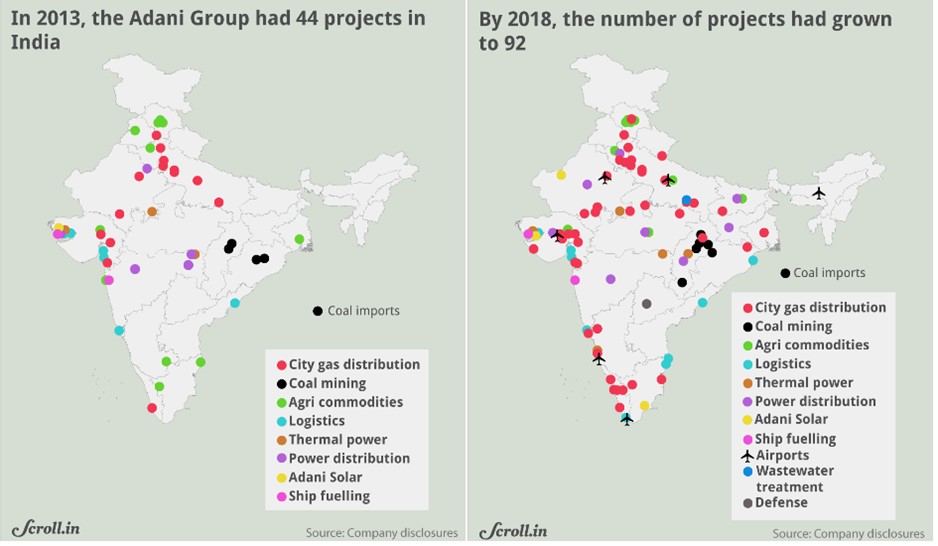

Unlike other large conglomerates such as Reliance Industries and Tata Group, that have a family group history tracing back a century or more, Adani’s ascent has been as recent as the last 10 years coinciding with the rise of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The corporate tycoon has been a zealous champion of Modi’s agenda, aligning his interest with those of the premier’s, predominantly in infrastructure and domestic manufacturing. Between 2014 and 2019, Adani’s net worth increased over 120% from USD 7.1bn to USD 15.7bn while his companies expanded their presence across India (c. 260 cities) vs previously being concentrated in the Gujrat district. By 2022 Gautam Adani was the world’s second richest man (net worth c. USD 150bn) surpassing Amazon CEO – Jeff Bezos.

The pace of Adani’s growth and his proximity to Modi, however, has been viewed with increasing scepticism bordering on cronyism. Criticism against the conglomerate grew in 2019 when the Modi government awarded six airport bids to the Adani Group despite it being inexperienced in airport management and against objections flagged by the finance ministry and NITI Aayog (National Institution for Transforming India).

India has an urgent need to boost its urban infrastructure; a 2021 world bank report estimates that India will need to invest USD 840bn over the next 15 years – an average of USD 55bn per annum to effectively meet the needs of its fast-growing urban population and remain competitive on a global scale. Given this backdrop, strong corporate-state alliances are critical to meet the needs gap and help create essential jobs.

In India, not unlike other emerging market (EM) economies, alignment and influence with reigning politicians is the norm for large conglomerates especially in critical sectors like infrastructure where the ruling government has much discretion over business activity. The culture awards players a monopolistic edge over peers however, fundamentally degenerates competition, discourages innovation, widens disparities, and slows growth. Further, the outcome of the State’s agenda and at times its stability precariously rests on the fate of a handful of players exposing broader systemic risks. This has been evidenced in recent weeks as opposition parties emboldened by allegations against the Adani Group used it to malign the ruling govt. of broader corruption claims.

All that is ‘green’ is not ‘clean’

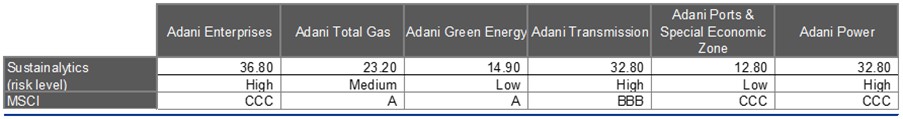

Adani is also a critical player in India’s transition to a green economy with the group’s plans to invest USD 70bn in solar, wind and other green energy projects over the next decade. Initially building his empire through coal mining and heavy industries, Adani quickly recognized the promise of renewable energy for growth and profitability. The firm used investments in renewable energy not only to capitalise on domestic govt incentives promoting self-reliance but also to garner more a favourable view in global capital markets. The Adani Green Energy Limited is rated ‘A’ by MSCI and ‘low risk’ by Sustainalytics (morningstar) and has raised millions in investment on account of its strong alignment with key UN sustainable development goals (SDG).

Source: Sustainalytics, MSCI ESG

The companies’ have recently been under review by global rating agencies following allegations of significant governance lapses. However, environmental advocates claim that the companies were never ‘green’ to begin with. Concerns about the group’s debt load, related party deals, and speculative transfers of money raised by the green energy arm back towards building more coal fired power plants or more coal mines (high ESG risk rated businesses) have long overshadowed the company. Despite this, the business was able to grow astronomically through local and international funding, due to a clever web of lofty sustainable infrastructure and de-risked value-creation claims. Therein, lies the myopic view with which investors can sometimes treat the ‘ESG’ acronym. Where corporate governance is interesting but still takes a back seat when compared to seemingly ‘green’ environmental projects. The business’s exploitative practises highlight the importance of a more holistic awareness and inclusion of ESG risks for investors when considering funding for such projects.

To meet its’ net zero goals by 2070, India requires investment of USD 160bn annually through 2030, roughly triple today’s levels, according to the International Energy Agency. A large part of this will be driven by the domestic private sector given the gap in govt’s capex budget and a much smaller, albeit growing, fraction of foreign direct investments. Executives at large organizations have thus far been happy to oblige, with Reliance Industries’s Mukesh Ambani and JSW Group’s Sajjan Jindal, along with energy giants such as Tata Group rushing to champion the shift to a cleaner future. Adani’s fall, if it occurs, will likely encourage other players to come forward, providing investors with more lucrative opportunities to invest in this space. The scandal however is also likely to increase scrutiny on Indian firms looking to raise ESG centric capital and possibly slowing down the transition.

The momentum trap

Like many other EM countries, the Indian stock market is dominated by tactical investors who routinely punt on stocks with low durability scores, expensive valuations but high momentum to beat market returns. The concentrated nature of the index, with the top 20 companies comprising c. 65% market cap, compounds their influence and entraps not only novice retail investors but large passive and index-oriented funds into an eventual spiral of mean reversion and significant losses.

Over the last two years to November 2022, the Adani companies had enjoyed a strong rally run contributing approximately 50% of the MSCI India’s 9.5% local currency return for the 12 months ending November 2022 and trading at multiples >300x for several of the underlying businesses. The result was a disproportionate impact on the performance of active fundamental investors who shied away from these stocks on account of their low liquidity, high valuations, unsustainable debt structure and governance concerns vs passive indexes and large billion-dollar funds with tighter tracking error constraints.

The fortunes have reversed in 2023, with the companies falling upwards of 30% since the start of this year. Minority investors in these instances have faced damages not only due to a strong bearish momentum but also the concentrated ownership structure, low levels of liquidity and trading bans enacted by exchanges (where applicable). By contrast, performance of Lonsec rated regional Indian equity managers has benefitted on a benchmark relative basis for the month ending January 2023. The share price meltdown of Adani companies’ yet again highlights the risks of fundamentally detached momentum trading in the generally opaque and more concentrated EM universe.

India Avenue asset management (Nov 2022 letter)

India – destination one for investors?

The Indian equity market has enjoyed a tremendous bull run over the last few years, contributed in part by China’s draconian Covid zero policy, and the market, economic and political woes of other key regions in the EM cohort. In many ways India has been considered a haven relative to its peers and has increasingly been pitted against China as the most likely driver of global economic growth for the next decade. Indeed, India was cited as one of the key economies for managers to visit or gain additional exposure to in 2023 (Lonsec annual review 2022 – Global Emerging Markets and Regional Asia managers).

Since the release of the report, the Adani ordeal has cost millions of dollars in investment losses to the likes of the Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF), Vanguard’s Emerging Markets Share Index fund, MLC’s MySuper Growth option etc. Several others in the debt space, including Blackrock and Citi Group, have been impacted as yields on its bonds have soared double digit highs. More broadly, the extent of its impact on the economy and Modi’s government is yet to fully unfold.

Although the broader Indian market has demonstrated resilience in recent weeks, the scandal is a stark reminder that India, not dissimilar to other EM countries, has several weak seams in its economic fabric. Which in the absence of strong checks and balances may be readily exploited by rapacious corporates to their advantage and to the detriment of outside investors.

For the nation, this presents an opportunity for reforms to the business, investing and regulatory practices to restore investor confidence and increase global competitiveness. For investors, it reinforces the importance of understanding and discounting country specific risks and incorporating sound corporate governance analysis and valuation discipline when it comes to stock picking.

This information is for personal, non-commercial purposes only and is not intended to be financial product advice. ©2023 Lonsec Research Pty Ltd. All rights reserved. You may not reproduce, transmit, disseminate, sell, or publish this information without the written consent of Lonsec Research Pty Ltd (Lonsec Research). This information may also contain third party material that is subject to copyright. To the extent that copyright subsists in a third party it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material. This information has been prepared in good faith and is believed to be reliable at the time it was prepared, however, no representation, warranty or undertaking is given or made in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented, which is drawn from third parties information not verified by Lonsec Research and is subject to change without notice. Lonsec Research assumes no obligation to update this document following publication. Except for any liability which cannot be excluded, Lonsec Research, its directors, officers, representatives, and agents disclaim all liability for any error or inaccuracy in, misstatement or omission from, this document or any loss or damage suffered by the reader or any other person as a consequence of relying upon it.